Postmodernism Is a Philosophy of Art That Came to the Fore After the Second World War

Postmodernism is an intellectual stance or style of soapbox[one] [2] divers by an attitude of skepticism toward what it considers equally the grand narratives and ideologies of modernism, too as opposition to epistemic certainty and the stability of meaning.[3] [4] Claims to objective fact are dismissed as naive realism.[4] [5] Postmodernism is characterized by self-referentiality, epistemological relativism, moral relativism, pluralism, irony, irreverence, and eclecticism;[iv] it rejects the "universal validity" of binary oppositions, stable identity, hierarchy, and categorization.[half-dozen] [7]

Postmodernism developed in the mid-twentieth century as a rejection of modernism[eight] [ix] [10] [11] and was so extended across many disciplines.[12] [13] Postmodernism is associated with deconstructionism and post-structuralism.[4] Diverse authors take criticized postmodernism as promoting obscurantism, as abandoning Enlightenment rationalism and scientific rigor, and as adding nothing to analytical or empirical knowledge.[14] [fifteen] [sixteen] [17] [eighteen] [19]

Definition [edit]

Postmodernism is an intellectual stance or style of discourse[1] [2] which challenges worldviews associated with Enlightenment rationality dating back to the 17th century.[four] Postmodernism is associated with relativism and a focus on ideology in the maintenance of economic and political power.[iv] Postmodernists are "skeptical of explanations which claim to be valid for all groups, cultures, traditions, or races, and instead focuses on the relative truths of each person".[xx] Information technology considers "reality" to be a mental construct.[20] Postmodernism rejects the possibility of unmediated reality or objectively-rational noesis, asserting that all interpretations are contingent on the perspective from which they are made;[5] claims to objective fact are dismissed every bit naive realism.[4]

Postmodern thinkers frequently draw noesis claims and value systems every bit contingent or socially-conditioned, describing them equally products of political, historical, or cultural discourses and hierarchies.[four] Accordingly, postmodern thought is broadly characterized by tendencies to cocky-referentiality, epistemological and moral relativism, pluralism, and blasphemy.[4] Postmodernism is often associated with schools of thought such every bit deconstruction and post-structuralism.[4] Postmodernism relies on critical theory, which considers the furnishings of ideology, society, and history on culture.[21] Postmodernism and critical theory commonly criticize universalist ideas of objective reality, morality, truth, human nature, reason, linguistic communication, and social progress.[4]

Initially, postmodernism was a fashion of discourse on literature and literary criticism, commenting on the nature of literary text, meaning, author and reader, writing, and reading.[8] Postmodernism developed in the mid- to late-twentieth century across many scholarly disciplines every bit a departure or rejection of modernism.[ix] [x] [11] [12] [13] As a critical practice, postmodernism employs concepts such as hyperreality, simulacrum, trace, and departure, and rejects abstract principles in favor of directly experience.[20]

Origins of term [edit]

The term postmodern was first used in 1870.[22] John Watkins Chapman suggested "a Postmodern style of painting" as a manner to depart from French Impressionism.[23] J. M. Thompson, in his 1914 article in The Hibbert Journal (a quarterly philosophical review), used it to depict changes in attitudes and beliefs in the critique of religion, writing: "The raison d'être of Post-Modernism is to escape from the double-mindedness of Modernism by being thorough in its criticism by extending information technology to faith besides equally theology, to Cosmic feeling besides as to Catholic tradition."[24]

In 1942 H. R. Hays described postmodernism as a new literary form.[25]

In 1926, Bernard Iddings Bong, president of St. Stephen's Higher (now Bard College), published Postmodernism and Other Essays, marking the start use of the term to describe the historical period post-obit Modernity.[26] [27] The essay criticizes the lingering socio-cultural norms, attitudes, and practices of the Historic period of Enlightenment. It too forecasts the major cultural shifts toward Postmodernity and (Bell existence an Anglican Episcopal priest[28] [29]) suggests orthodox religion every bit a solution.[30] Still, the term postmodernity was first used as a general theory for a historical movement in 1939 past Arnold J. Toynbee: "Our own Post-Modern Historic period has been inaugurated by the general war of 1914–1918".[31]

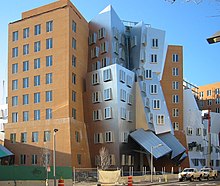

In 1949 the term was used to draw a dissatisfaction with modern architecture and led to the postmodern architecture movement[32] in response to the modernist architectural motility known as the International Style. Postmodernism in architecture was initially marked past a re-emergence of surface ornament, reference to surrounding buildings in urban settings, historical reference in decorative forms (eclecticism), and not-orthogonal angles.[33]

Writer Peter Drucker suggested the transformation into a post-modern world that happened between 1937 and 1957 and described information technology equally a "nameless era" characterized equally a shift to a conceptual world based on design, purpose, and process rather than a mechanical crusade. This shift was outlined by iv new realities: the emergence of an Educated Society, the importance of international development, the reject of the nation-state, and the plummet of the viability of non-Western cultures.[34]

In 1971, in a lecture delivered at the Institute of Contemporary Art, London, Mel Bochner described "post-modernism" in art as having started with Jasper Johns, "who first rejected sense-information and the singular signal-of-view as the ground for his art, and treated art equally a disquisitional investigation".[35]

In 1996, Walter Truett Anderson described postmodernism every bit belonging to one of four typological world views which he identified as:

- Neo-romantic, in which truth is institute through attaining harmony with nature or spiritual exploration of the inner self.[36]

- Postmodern-ironist, which sees truth as socially constructed.

- Scientific-rational, in which truth is divers through methodical, disciplined inquiry.

- Social-traditional, in which truth is found in the heritage of American and Western civilisation.

History [edit]

The basic features of what is now called postmodernism can exist found as early as the 1940s, most notably in the piece of work of artists such as Jorge Luis Borges.[37] However, well-nigh scholars today concur postmodernism began to compete with modernism in the late 1950s and gained clout over it in the 1960s.[38]

The primary features of postmodernism typically include the ironic play with styles, citations, and narrative levels,[39] [40] a metaphysical skepticism or nihilism towards a "grand narrative" of Western culture,[41] and a preference for the virtual at the expense of the Real (or more accurately, a key questioning of what 'the existent' constitutes).[42]

Since the tardily 1990s, in that location has been a growing sentiment in popular culture and in academia that postmodernism "has gone out of fashion".[43] Others debate that postmodernism is dead in the context of current cultural production.[44] [45] [46]

Theories and derivatives [edit]

Structuralism and mail service-structuralism [edit]

Structuralism was a philosophical motion developed by French academics in the 1950s, partly in response to French existentialism,[47] and oft interpreted in relation to modernism and loftier modernism. Thinkers who have been chosen "structuralists" include the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, the linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, the Marxist philosopher Louis Althusser, and the semiotician Algirdas Greimas. The early writings of the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan and the literary theorist Roland Barthes accept also been chosen "structuralist". Those who began as structuralists simply became post-structuralists include Michel Foucault, Roland Barthes, Jean Baudrillard, and Gilles Deleuze. Other post-structuralists include Jacques Derrida, Pierre Bourdieu, Jean-François Lyotard, Julia Kristeva, Hélène Cixous, and Luce Irigaray. The American cultural theorists, critics, and intellectuals whom they influenced include Judith Butler, John Fiske, Rosalind Krauss, Avital Ronell, and Hayden White.

Like structuralists, post-structuralists commencement from the assumption that people's identities, values, and economic conditions make up one's mind each other rather than having intrinsic backdrop that can be understood in isolation.[48] Thus the French structuralists considered themselves to exist espousing relativism and constructionism. But they nevertheless tended to explore how the subjects of their study might exist described, reductively, equally a prepare of essential relationships, schematics, or mathematical symbols. (An case is Claude Lévi-Strauss's algebraic formulation of mythological transformation in "The Structural Written report of Myth"[49]).

Postmodernism entails reconsideration of the entire Western value arrangement (love, marriage, popular culture, shift from an industrial to a service economic system) that took place since the 1950s and 1960s, with a height in the Social Revolution of 1968—are described with the term postmodernity,[fifty] every bit opposed to postmodernism, a term referring to an stance or motion.[51] Postal service-structuralism is characterized past new ways of thinking through structuralism, contrary to the original form.[52]

Deconstruction [edit]

One of the most well-known postmodernist concerns is deconstruction, a theory for philosophy, literary criticism, and textual analysis developed by Jacques Derrida.[53] Critics accept insisted that Derrida'south work is rooted in a statement institute in Of Grammatology: " Il n'y a pas de hors-texte " ('in that location is nothing outside the text'). Such critics misinterpret the argument as denying whatsoever reality outside of books. The argument is actually part of a critique of "inside" and "outside" metaphors when referring to the text, and is a corollary to the observation that there is no "inside" of a text as well.[54] This attention to a text'south unacknowledged reliance on metaphors and figures embedded within its discourse is characteristic of Derrida'due south approach. Derrida'due south method sometimes involves demonstrating that a given philosophical discourse depends on binary oppositions or excluding terms that the discourse itself has declared to exist irrelevant or inapplicable. Derrida's philosophy inspired a postmodern movement chosen deconstructivism amidst architects, characterized by a pattern that rejects structural "centers" and encourages decentralized play among its elements. Derrida discontinued his involvement with the movement subsequently the publication of his collaborative project with architect Peter Eisenman in Chora L Works: Jacques Derrida and Peter Eisenman.[55]

Post-postmodernism [edit]

The connection between postmodernism, posthumanism, and cyborgism has led to a claiming to postmodernism, for which the terms Post-postmodernism and postpoststructuralism were starting time coined in 2003:[56] [57]

In some sense, we may regard postmodernism, posthumanism, poststructuralism, etc., as being of the 'cyborg age' of mind over body. Deconference was an exploration in post-cyborgism (i.e. what comes after the postcorporeal era), and thus explored issues of postpostmodernism, postpoststructuralism, and the like. To understand this transition from 'pomo' (cyborgism) to 'popo' (postcyborgism) we must outset understand the cyborg era itself.[58]

More than recently metamodernism, post-postmodernism and the "expiry of postmodernism" accept been widely debated: in 2007 Andrew Hoberek noted in his introduction to a special issue of the periodical Twentieth-Century Literature titled "Afterwards Postmodernism" that "declarations of postmodernism's demise have go a critical commonplace". A small-scale group of critics has put along a range of theories that aim to describe civilization or society in the alleged aftermath of postmodernism, well-nigh notably Raoul Eshelman (performatism), Gilles Lipovetsky (hypermodernity), Nicolas Bourriaud (altermodern), and Alan Kirby (digimodernism, formerly called pseudo-modernism). None of these new theories or labels accept so far gained very widespread credence. Sociocultural anthropologist Nina Müller-Schwarze offers neostructuralism as a possible management.[59] The exhibition Postmodernism – Style and Subversion 1970–1990 at the Victoria and Albert Museum (London, 24 September 2011 – fifteen Jan 2012) was billed as the first show to document postmodernism equally a historical movement.

Philosophy [edit]

In the 1970s a grouping of poststructuralists in French republic adult a radical critique of modern philosophy with roots discernible in Nietzsche, Kierkegaard, and Heidegger, and became known as postmodern theorists, notably including Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, Jean-François Lyotard, Jean Baudrillard, and others. New and challenging modes of thought and writing pushed the development of new areas and topics in philosophy. By the 1980s, this spread to America (Richard Rorty) and the world.[60]

Jacques Derrida [edit]

Jacques Derrida was a French-Algerian philosopher all-time known for developing a form of semiotic assay known as deconstruction, which he discussed in numerous texts, and developed in the context of phenomenology.[61] [62] [63] He is ane of the major figures associated with mail service-structuralism and postmodern philosophy.[64] [65] [66]

Derrida re-examined the fundamentals of writing and its consequences on philosophy in full general; sought to undermine the linguistic communication of "presence" or metaphysics in an analytical technique which, offset equally a betoken of difference from Heidegger's notion of Destruktion, came to exist known as deconstruction.[67]

Michel Foucault [edit]

Michel Foucault was a French philosopher, historian of ideas, social theorist, and literary critic. Showtime associated with structuralism, Foucault created an oeuvre that today is seen as belonging to mail service-structuralism and to postmodern philosophy. Considered a leading figure of French theory [fr], his work remains fruitful in the English language-speaking academic earth in a large number of sub-disciplines. The Times Higher Education Guide described him in 2009 every bit the almost cited author in the humanities.[68]

Michel Foucault introduced concepts such as discursive regime, or re-invoked those of older philosophers like episteme and genealogy in gild to explicate the relationship between meaning, power, and social behavior inside social orders (encounter The Order of Things, The Archaeology of Noesis, Bailiwick and Punish, and The History of Sexuality).[69] [lxx] [71] [72]

Jean-François Lyotard [edit]

Influenced past Nietzsche,[73] Jean-François Lyotard is credited with being the beginning to use the term in a philosophical context, in his 1979 work The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Noesis. In it, he follows Wittgenstein'southward language games model and speech act theory, contrasting two different language games, that of the expert, and that of the philosopher. He talks nigh the transformation of knowledge into information in the computer age and likens the transmission or reception of coded letters (information) to a position inside a linguistic communication game.[3]

Lyotard defined philosophical postmodernism in The Postmodern Status, writing: "Simplifying to the extreme, I define postmodern as incredulity towards metanarratives...." [74] where what he means past metanarrative is something like a unified, complete, universal, and epistemically certain story about everything that is. Postmodernists reject metanarratives because they reject the concept of truth that metanarratives presuppose. Postmodernist philosophers, in general, fence that truth is always contingent on historical and social context rather than being absolute and universal—and that truth is always partial and "at upshot" rather than beingness complete and sure.[3]

Richard Rorty [edit]

Richard Rorty argues in Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature that contemporary analytic philosophy mistakenly imitates scientific methods. In addition, he denounces the traditional epistemological perspectives of representationalism and correspondence theory that rely upon the independence of knowers and observers from phenomena and the passivity of natural phenomena in relation to consciousness.

Jean Baudrillard [edit]

Jean Baudrillard, in Simulacra and Simulation, introduced the concept that reality or the principle of the Real is short-circuited by the interchangeability of signs in an era whose chatty and semantic acts are dominated past electronic media and digital technologies. For Baudrillard, "simulation is no longer that of a territory, a referential being or a substance. It is the generation by models of a real without origin or reality: a hyperreal."[75]

Fredric Jameson [edit]

Fredric Jameson gear up along one of the first expansive theoretical treatments of postmodernism as a historical period, intellectual trend, and social phenomenon in a series of lectures at the Whitney Museum, later expanded as Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Belatedly Commercialism (1991).[76]

Douglas Kellner [edit]

In Analysis of the Journeying, a periodical birthed from postmodernism, Douglas Kellner insists that the "assumptions and procedures of modern theory" must be forgotten. Extensively, Kellner analyzes the terms of this theory in real-life experiences and examples.[77] Kellner used science and technology studies every bit a major office of his analysis; he urged that the theory is incomplete without information technology. The scale was larger than just postmodernism alone; information technology must be interpreted through cultural studies where science and engineering studies play a huge function. The reality of the September 11 attacks on the United States of America is the catalyst for his explanation. In response, Kellner continues to examine the repercussions of understanding the effects of the 11 September attacks. He questions if the attacks are only able to be understood in a limited course of postmodern theory due to the level of irony.[78]

The conclusion he depicts is elementary: postmodernism, as most use it today, will decide what experiences and signs in one's reality will be one's reality every bit they know it.[79]

Manifestations [edit]

Architecture [edit]

Modern Architecture, as established and developed past Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier, was focused on:

- the attempted harmony of course and part;[80] and,

- the dismissal of "frivolous ornament."[81] [82] [ page needed ]

- the pursuit of a perceived platonic perfection;

They argued for compages that represented the spirit of the historic period equally depicted in cutting-edge technology, be it airplanes, cars, sea liners, or even supposedly artless grain silos.[83] Modernist Ludwig Mies van der Rohe is associated with the phrase "less is more".

Critics of Modernism accept:

- argued that the attributes of perfection and minimalism are themselves subjective;

- pointed out anachronisms in mod thought; and,

- questioned the benefits of its philosophy.[84] [ total citation needed ]

The intellectual scholarship regarding postmodernism and architecture is closely linked with the writings of critic-turned-builder Charles Jencks, beginning with lectures in the early 1970s and his essay "The Rise of Mail Modern Compages" from 1975.[85] His magnum opus, nonetheless, is the book The Linguistic communication of Post-Modern Architecture, first published in 1977, and since running to seven editions.[86] Jencks makes the point that Mail service-Modernism (like Modernism) varies for each field of fine art, and that for compages it is not just a reaction to Modernism but what he terms double coding: "Double Coding: the combination of Modern techniques with something else (commonly traditional building) in society for compages to communicate with the public and a concerned minority, usually other architects."[87] In their volume, "Revisiting Postmodernism", Terry Farrell and Adam Furman argue that postmodernism brought a more than joyous and sensual experience to the civilisation, especially in architecture.[88]

Fine art [edit]

Postmodern fine art is a body of art movements that sought to contradict some aspects of modernism or some aspects that emerged or developed in its aftermath. Cultural production manifesting equally intermedia, installation fine art, conceptual fine art, deconstructionist display, and multimedia, particularly involving video, are described as postmodern.[89]

Graphic pattern [edit]

Early mention of postmodernism every bit an element of graphic pattern appeared in the British mag, "Design".[90] A characteristic of postmodern graphic design is that "retro, techno, punk, grunge, beach, parody, and pastiche were all conspicuous trends. Each had its own sites and venues, detractors and advocates."[91]

Literature [edit]

Jorge Luis Borges' (1939) curt story "Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote", is often considered as predicting postmodernism[92] and is a paragon of the ultimate parody.[93] Samuel Beckett is also considered an important precursor and influence. Novelists who are normally continued with postmodern literature include Vladimir Nabokov, William Gaddis, Umberto Eco, Pier Vittorio Tondelli, John Hawkes, William S. Burroughs, Kurt Vonnegut, John Barth, Jean Rhys, Donald Barthelme, E. L. Doctorow, Richard Kalich, Jerzy Kosiński, Don DeLillo, Thomas Pynchon[94] (Pynchon's piece of work has likewise been described as high mod[95]), Ishmael Reed, Kathy Acker, Ana Lydia Vega, Jáchym Topol and Paul Auster.

In 1971, the Arab-American scholar Ihab Hassan published The Dismemberment of Orpheus: Toward a Postmodern Literature, an early on work of literary criticism from a postmodern perspective that traces the development of what he calls "literature of silence" through Marquis de Sade, Franz Kafka, Ernest Hemingway, Samuel Beckett, and many others, including developments such as the Theatre of the Absurd and the nouveau roman.

In Postmodernist Fiction (1987), Brian McHale details the shift from modernism to postmodernism, arguing that the former is characterized past an epistemological dominant and that postmodern works have developed out of modernism and are primarily concerned with questions of ontology.[96] McHale's second book, Constructing Postmodernism (1992), provides readings of postmodern fiction and some contemporary writers who become nether the label of cyberpunk. McHale's "What Was Postmodernism?" (2007)[97] follows Raymond Federman's lead in now using the past tense when discussing postmodernism.

Music [edit]

Jonathan Kramer has written that avant-garde musical compositions (which some would consider modernist rather than postmodernist) "defy more than seduce the listener, and they extend by potentially unsettling means the very idea of what music is."[98] In the 1960s, composers such as Terry Riley, Henryk Górecki, Bradley Joseph, John Adams, Steve Reich, Philip Glass, Michael Nyman, and Lou Harrison reacted to the perceived elitism and dissonant sound of atonal bookish modernism past producing music with uncomplicated textures and relatively consonant harmonies, whilst others, about notably John Muzzle challenged the prevailing narratives of beauty and objectivity common to Modernism.

Author on postmodernism, Dominic Strinati, has noted, it is too of import "to include in this category the so-called 'art rock' musical innovations and mixing of styles associated with groups like Talking Heads, and performers like Laurie Anderson, together with the cocky-witting 'reinvention of disco' by the Pet Shop Boys".[99]

In the late-20th century, advanced academics labelled American singer Madonna, as the "personification of the postmodern",[100] with Christian writer Graham Cray saying that "Madonna is perhaps the most visible example of what is called post-modernism",[101] and Martin Amis described her every bit "perhaps the near postmodern personage on the planet".[101] She was also suggested by banana professor Olivier Sécardin of Utrecht University to epitomise postmodernism.[102]

Urban planning [edit]

Modernism sought to design and programme cities that followed the logic of the new model of industrial mass production; reverting to large-scale solutions, aesthetic standardisation, and prefabricated design solutions.[103] Modernism eroded urban living past its failure to recognise differences and aim towards homogeneous landscapes (Simonsen 1990, 57). Jane Jacobs' 1961 book The Death and Life of Keen American Cities [104] was a sustained critique of urban planning as it had developed inside Modernism and marked a transition from modernity to postmodernity in thinking about urban planning (Irving 1993, 479).

The transition from Modernism to Postmodernism is oft said to have happened at 3:32 pm on 15 July in 1972, when Pruitt–Igoe, a housing development for depression-income people in St. Louis designed by architect Minoru Yamasaki, which had been a prize-winning version of Le Corbusier's 'machine for mod living,' was deemed uninhabitable and was torn down (Irving 1993, 480). Since and then, Postmodernism has involved theories that embrace and aim to create diversity. It exalts doubtfulness, flexibility and change (Hatuka & D'Hooghe 2007) and rejects utopianism while embracing a utopian mode of thinking and acting.[105] Postmodernity of 'resistance' seeks to deconstruct Modernism and is a critique of the origins without necessarily returning to them (Irving 1993, 60). As a issue of Postmodernism, planners are much less inclined to lay a firm or steady claim to there being 1 single 'correct way' of engaging in urban planning and are more open to different styles and ideas of 'how to programme' (Irving 474).[103] [105] [106] [107]

The postmodern approach to understanding the metropolis were pioneered in the 1980s by what could exist called the "Los Angeles School of Urbanism" centered on the UCLA's Urban Planning Department in the 1980s, where contemporary Los Angeles was taken to be the postmodern city par excellence, contra posed to what had been the dominant ideas of the Chicago School formed in the 1920s at the University of Chicago, with its framework of urban ecology and emphasis on functional areas of use within a urban center, and the concentric circles to understand the sorting of different population groups.[108] Edward Soja of the Los Angeles School combined Marxist and postmodern perspectives and focused on the economic and social changes (globalization, specialization, industrialization/deindustrialization, Neo-Liberalism, mass migration) that lead to the creation of large urban center-regions with their patchwork of population groups and economic uses.[108] [109]

Criticisms [edit]

Criticisms of postmodernism are intellectually diverse, including the argument that postmodernism is meaningless and promotes obscurantism.

In part in reference to post-modernism, conservative English philosopher Roger Scruton wrote, "A writer who says that there are no truths, or that all truth is 'merely relative,' is asking you not to believe him. Then don't."[110] Similarly, Dick Hebdige criticized the vagueness of the term, enumerating a long listing of otherwise unrelated concepts that people have designated as postmodernism, from "the décor of a room" or "a 'scratch' video", to fright of nuclear armageddon and the "implosion of meaning", and stated that annihilation that could signify all of those things was "a buzzword".[111]

The linguist and philosopher Noam Chomsky has said that postmodernism is meaningless because information technology adds zip to analytical or empirical knowledge. He asks why postmodernist intellectuals practice not respond like people in other fields when asked, "what are the principles of their theories, on what evidence are they based, what do they explain that wasn't already obvious, etc.?...If [these requests] can't exist met, then I'd suggest recourse to Hume's advice in like circumstances: 'to the flames'."[112]

Christian philosopher William Lane Craig has said "The idea that we live in a postmodern civilisation is a myth. In fact, a postmodern culture is an impossibility; it would be utterly unliveable. People are not relativistic when it comes to matters of scientific discipline, engineering, and technology; rather, they are relativistic and pluralistic in matters of religion and ideals. Just, of course, that's not postmodernism; that's modernism!"[113]

American writer Thomas Pynchon targeted postmodernism as an object of derision in his novels, openly mocking postmodernist discourse.[114]

American academic and aesthete Camille Paglia has said:

The end consequence of 4 decades of postmodernism permeating the art world is that at that place is very little interesting or important work existence done right now in the fine arts. The irony was a assuming and creative posture when Duchamp did it, but it is now an utterly banal, exhausted, and tedious strategy. Immature artists have been taught to be "cool" and "hip" and thus painfully self-conscious. They are not encouraged to be enthusiastic, emotional, and visionary. They accept been cutting off from artistic tradition by the crippled skepticism almost history that they have been taught past ignorant and solipsistic postmodernists. In curt, the fine art world will never revive until postmodernism fades away. Postmodernism is a plague upon the mind and the center.[115]

High german philosopher Albrecht Wellmer has said that "postmodernism at its all-time might be seen equally a self-critical – a sceptical, ironic, only withal unrelenting – form of modernism; a modernism beyond utopianism, scientism and foundationalism; in short a mail service-metaphysical modernism."[116]

A formal, bookish critique of postmodernism tin can be found in Across the Hoax by physics professor Alan Sokal and in Fashionable Nonsense past Sokal and Belgian physicist Jean Bricmont, both books discussing the so-called Sokal matter. In 1996, Sokal wrote a deliberately nonsensical commodity[117] in a style similar to postmodernist articles, which was accepted for publication by the postmodern cultural studies periodical, Social Text. On the aforementioned day of the release he published another article in a unlike journal explaining the Social Text article hoax.[118] [119] The philosopher Thomas Nagel has supported Sokal and Bricmont, describing their book Fashionable Nonsense every bit consisting largely of "extensive quotations of scientific gibberish from name-brand French intellectuals, together with eerily patient explanations of why information technology is gibberish,"[120] and agreeing that "there does seem to exist something virtually the Parisian scene that is particularly hospitable to reckless verbosity."[121]

Zimbabwean-born British Marxist Alex Callinicos says that postmodernism "reflects the disappointed revolutionary generation of '68, and the incorporation of many of its members into the professional and managerial 'new middle class'. It is all-time read as a symptom of political frustration and social mobility rather than every bit a significant intellectual or cultural phenomenon in its own correct."[122]

Analytic philosopher Daniel Dennett said, "Postmodernism, the school of 'thought' that proclaimed 'There are no truths, only interpretations' has largely played itself out in applesauce, but it has left backside a generation of academics in the humanities disabled by their distrust of the very idea of truth and their boldness for prove, settling for 'conversations' in which nobody is incorrect and nothing can be confirmed, only asserted with whatsoever fashion you can muster."[123]

American historian Richard Wolin traces the origins of postmodernism to intellectual roots in fascism, writing "postmodernism has been nourished by the doctrines of Friedrich Nietzsche, Martin Heidegger, Maurice Blanchot, and Paul de Human—all of whom either prefigured or succumbed to the proverbial intellectual fascination with fascism."[124]

Daniel A. Farber and Suzanna Sherry criticised postmodernism for reducing the complexity of the modern world to an expression of power and for undermining truth and reason:

If the modern era begins with the European Enlightenment, the postmodern era that captivates the radical multiculturalists begins with its rejection. According to the new radicals, the Enlightenment-inspired ideas that take previously structured our world, especially the legal and academic parts of it, are a fraud perpetrated and perpetuated by white males to consolidate their ain power. Those who disagree are non simply blind but bigoted. The Enlightenment's goal of an objective and reasoned basis for cognition, merit, truth, justice, and the like is an impossibility: "objectivity," in the sense of standards of judgment that transcend individual perspectives, does non exist. Reason is just some other code word for the views of the privileged. The Enlightenment itself simply replaced i socially constructed view of reality with another, mistaking ability for noesis. There is naught merely power.[125]

Richard Caputo, William Epstein, David Stoesz & Bruce Thyer consider postmodernism to exist a "dead-end in social work epistemology." They write:

Postmodernism continues to accept a detrimental influence on social work, questioning the Enlightenment, criticizing established research methods, and challenging scientific authority. The promotion of postmodernism by editors of Social Piece of work and the Periodical of Social Work Pedagogy has elevated postmodernism, placing it on a par with theoretically guided and empirically based inquiry. The inclusion of postmodernism in the 2008 Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards of the Council on Social Piece of work Educational activity and its 2015 sequel further erode the knowledge-building capacity of social work educators. In relation to other disciplines that have exploited empirical methods, social work's stature will continue to ebb until postmodernism is rejected in favor of scientific methods for generating knowledge.[126]

H. Sidky pointed out what he sees equally several inherent flaws of a postmodern antiscience perspective, including the confusion of the authorisation of science (evidence) with the scientist conveying the knowledge; its cocky-contradictory claim that all truths are relative; and its strategic ambiguity. He sees 21st-century anti-scientific and pseudo-scientific approaches to noesis, especially in the United States, as rooted in a postmodernist "decades-long academic assault on science:"

Many of those indoctrinated in postmodern anti-science went on to become conservative political and religious leaders, policymakers, journalists, periodical editors, judges, lawyers, and members of city councils and school boards. Sadly, they forgot the lofty ideals of their teachers, except that science is bogus.[127]

Criticism past thinkers who were associated with postmodernism themselves [edit]

The French psychotherapist and philosopher, Félix Guattari, rejected its theoretical assumptions by arguing that the structuralist and postmodernist visions of the world were not flexible enough to seek explanations in psychological, social, and environmental domains at the aforementioned time.[128]

In an interview, Jean Baudrillard noted: "[ Transmodernism etc] are ameliorate terms than "postmodernism". It is non about modernity; it is most every organisation that has developed its fashion of expression to the extent that information technology surpasses itself and its own logic. This is what I am trying to analyze." "There is no longer any ontologically underground substance. I perceive this to be nihilism rather than postmodernism. To me, nihilism is a good thing – I am a nihilist, not a postmodernist."[129]

See also [edit]

References [edit]

- ^ a b Nuyen, A.T., 1992. The Function of Rhetorical Devices in Postmodernist Discourse. Philosophy & Rhetoric, pp.183–194.

- ^ a b Torfing, Jacob (1999). New theories of discourse : Laclau, Mouffe, and Z̆iz̆ek. Oxford, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland Malden, Mass: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN0-631-19557-2.

- ^ a b c Aylesworth, Gary (5 February 2015) [1st pub. 2005]. "Postmodernism". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. sep-postmodernism (Jump 2015 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d eastward f 1000 h i j k Duignan, Brian. "Postmodernism". Britannica.com . Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ^ a b Bryant, Ian; Rennie Johnston; Robin Usher (2004). Adult Education and the Postmodern Challenge: Learning Across the Limits. Routledge. p. 203.

- ^ "postmodernism". American Heritage Lexicon. Houghton, Mifflin, Harcourt. 2019. Archived from the original on 15 June 2018. Retrieved 5 May 2019 – via AHDictionary.com.

Of or relating to an intellectual stance often marked by eclecticism and irony and tending to reject the universal validity of such principles as bureaucracy, binary opposition, categorization, and stable identity.

- ^ Bauman, Zygmunt (1992). Intimations of postmodernity . London New York: Routledge. p. 26. ISBN978-0-415-06750-8.

- ^ a b Lyotard, Jean-François (1989). The Lyotard reader. Oxford, U.k. / Cambridge, Massachusetts: Blackwell. ISBN0-631-16339-five.

- ^ a b "postmodernism". Oxford Dictionary (American English language) – via oxforddictionaries.com.

- ^ a b Mura, Andrea (2012). "The Symbolic Function of Transmodernity". Language and Psychoanalysis. one (1): 68–87. doi:10.7565/landp.2012.0005.

- ^ a b "postmodern". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4th ed.). 2000. Archived from the original on 9 December 2008 – via Bartleby.com.

- ^ a b Hutcheon, Linda (2002). The politics of postmodernism. London New York: Routledge. ISBN978-0-203-42605-0.

- ^ a b Hatch, Mary (2013). System theory : modern, symbolic, and postmodern perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Printing. ISBN978-0-19-964037-9.

- ^ Hicks, Stephen (2011). Explaining postmodernism : skepticism and socialism from Rousseau to Foucault. Roscoe, Illinois: Ockham'south Razor Publishing. ISBN978-0-9832584-0-vii.

- ^ Brown, Callum (2013). Postmodernism for historians. London: Routledge. ISBN978-ane-315-83610-ii.

- ^ Bruner, Edward Chiliad. (1994). "Abraham Lincoln as Accurate Reproduction: A Critique of Postmodernism" (PDF). American Anthropologist. 96 (two): 397–415. doi:10.1525/aa.1994.96.ii.02a00070. JSTOR 681680. S2CID 161259515. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2020.

- ^ Callinicos, Alex (1989). Against postmodernism : a marxist critique. Cambridge: Polity Press. ISBN0-7456-0614-8.

- ^ Devigne, Robert (1994). "Introduction". Recasting conservatism : Oakeshott, Strauss, and the response to postmodernism. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Printing. ISBN0-300-06868-9.

- ^ Sokal, Alan; Bricmont, Jean (1999). Intellectual impostures : postmodern philosophers' abuse of science. London: Profile. ISBNi-86197-124-9.

- ^ a b c "Postmodernism Glossary". Faith and Reason. 11 September 1998. Retrieved x June 2019 – via PBS.org.

- ^ Kellner, Douglas (1995). Media culture : cultural studies, identity, and politics between the modern and the postmodern. London / New York: Routledge. ISBN0-415-10569-ii.

- ^ Welsch, Wolfgang; Sandbothe, Mike (1997). "Postmodernity as a Philosophical Concept". International Postmodernism. Comparative History of Literatures in European Languages. Vol. XI. p. 76. doi:10.1075/chlel.xi.07wel. ISBN978-90-272-3443-8.

- ^ Hassan, Ihab, The Postmodern Turn, Essays in Postmodern Theory and Civilization, Ohio University Printing, 1987. p. 12ff.

- ^ Thompson, J. Chiliad. "Post-Modernism," The Hibbert Journal. Vol XII No. 4, July 1914. p. 733

- ^ Dorsey, Arris (2018). Origins of Sociological Theory. Collier, Readale. p. 211. ISBN978-1-83947-426-2.

- ^ Merriam Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, 2004

- ^ Madsen, Deborah (1995). Postmodernism: A Bibliography. Amsterdam; Atlanta, Georgia: Rodopi.

- ^ Russell Kirk: American Conservative. University Press of Kentucky. 9 November 2015. ISBN9780813166209.

- ^ Russello, Gerald J. (25 Oct 2007). The Postmodern Imagination of Russell Kirk. University of Missouri Press. ISBN9780826265944 – via Google Books.

- ^ Bell, Bernard Iddings (1926). Postmodernism and Other Essays. Milwaukie: Morehouse Publishing Visitor.

- ^ Arnold J. Toynbee, A report of History, Book 5, Oxford Academy Press, 1961 [1939], p. 43.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, 2004

- ^ Seah, Isaac. "Postal service Modernism in Architecture".

- ^ Drucker, Peter F. (1957). Landmarks of Tomorrow. New York: Harper Brothers. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ^ Bochner, Mel (2008). Solar Organisation & Rest Rooms: Writings and Interviews 1965–2007. Usa: The MIT Press. p. 91. ISBN978-0-262-02631-four.

- ^ Anderson, Walter Truett (1996). The Fontana Postmodernism Reader.

- ^ See Barth, John: "The Literature of Exhaustion." The Atlantic Monthly, Baronial 1967, pp. 29–34.

- ^ Cf., for case, Huyssen, Andreas: After the Great Divide. Modernism, Mass Culture, Postmodernism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986, p. 188.

- ^ Come across Hutcheon, Linda: A Poetics of Postmodernism. History, Theory, Fiction. New York: Routledge, 1988, pp. 3–21

- ^ See McHale, Brian: Postmodern Fiction, London: Methuen, 1987.

- ^ See Lyotard, Jean-François, The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge, Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press 1984

- ^ See Baudrillard, Jean: "Simulacra and Simulations." In: Jean Baudrillard. Selected Writings. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1988, pp. 166–184.

- ^ Potter, Garry and Lopez, Jose (eds.): After Postmodernism: An Introduction to Disquisitional Realism. London: The Athlone Press 2001, p. iv.

- ^ Fjellestad, Danuta; Engberg, Maria (2013). "Toward a Concept of Postal service-Postmodernism or Lady Gaga'south Reconfigurations of Madonna". Reconstruction: Studies in Contemporary Culture. 12 (4). Archived from the original on 23 February 2013. DiVA 833886.

- ^ Kirby, Alan (2006). "The Expiry of Postmodernism and Across". Philosophy At present. 58: 34–37.

- ^ Gibbons, Alison (2017). "Postmodernism is dead. What comes adjacent?". TLS . Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- ^ Kurzweil, Edith (2017). The age of structuralism : from Lévi-Strauss to Foucault. London: Routledge. ISBN978-one-351-30584-6.

- ^ Lévi-Strauss, Claude (1963). Structural Anthropology (I ed.). U.s.: New York: Basic Books. p. 324. ISBN0-465-09516-X.

Lévi-Strauss, quoting D'Arcy Westworth Thompson states: "To those who question the possibility of defining the interrelations between entities whose nature is non completely understood, I shall answer with the following comment past a great naturalist: In a very large office of morphology, our essential task lies in the comparison of related forms rather than in the precise definition of each; and the deformation of a complicated figure may be a miracle easy of comprehension, though the effigy itself has to be left unanalyzed and undefined."

- ^ Lévi-Strauss, Claude. Anthropologie Structurale. Paris: Éditions Plon, 1958.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude. Structural Anthropology. Trans. Claire Jacobson and Brooke Grundfest Schoepf (New York: Bones Books, 1963), 228. - ^ "TRANS Nr. 11: Paul Michael Lützeler (St. Louis): From Postmodernism to Postcolonialism". inst.at.

- ^ Sarup, Madan (1993). An introductory guide to mail service-structuralism and postmodernism. Athens: University of Georgia Press. ISBN0-8203-1531-1.

- ^ Yilmaz, K (2010). "Postmodernism and its Claiming to the Subject of History: Implications for History Pedagogy". Educational Philosophy & Theory. 42 (vii): 779–795. doi:10.1111/j.1469-5812.2009.00525.x. S2CID 145695056.

- ^ Culler, Jonathan (2008). On deconstruction : theory and criticism after structuralism. London: Routledge. ISBN978-0-415-46151-1.

- ^ Derrida (1967), Of Grammatology, Function Ii, Introduction to the "Historic period of Rousseau," section two "...That Dangerous Supplement...", title, "The Exorbitant Question of Method", pp. 158–59, 163.

- ^ Peeters, Benoît. Derrida: A Biography, pp. 377–8, translated past Andrew Brown, Polity Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0-7456-5615-one

- ^ Mann, Steve (2003). "Decon2 (Decon Squared): Deconstructing Decontamination" (PDF). Leonardo. 36 (4): 285–290. doi:10.1162/002409403322258691. JSTOR 1577323. S2CID 57559253.

- ^ Campbell, Heidi A. (2006). "Postcyborg Ethics: A New Way to Speak of Engineering science". Explorations in Media Ecology. five (4): 279–296. doi:x.1386/eme.5.4.279_1.

- ^ Mann, Steve; Fung, James; Federman, Marking; Baccanico, Gianluca (2002). "PanopDecon: Deconstructing, decontaminating, and decontextualizing panopticism in the postcyborg era". Surveillance & Social club. 1 (3): 375–398. doi:10.24908/ss.v1i3.3346.

- ^ Müller Schwarze, Nina 2015 The Blood of Victoriano Lorenzo: An Ethnography of the Cholos of Northern Coclé Province. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Printing.

- ^ All-time, Steven; Kellner, Douglas (2 November 2001). "The Postmodern Plough in Philosophy: Theoretical Provocations and Normative Deficits". UCLA Graduate Schoolhouse of Education and Information Studies. UCLA. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ "Jacques Derrida". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. eleven October 2018. Retrieved fourteen May 2019.

- ^ McCance, Dawne (5 December 2014) [2009: Equinox]. Derrida on Religion: Thinker of Differance. Key thinkers in the written report of religion. London: Routledge. p. 7. ISBN978-1-317-49093-7. OCLC 960024707.

- ^ Peters, Michael A.; Biesta, Gert (2009). Derrida, Deconstruction, and the Politics of Didactics. New York: Peter Lang. p. 134. ISBN978-1-4331-0009-3. OCLC 314727596.

- ^ Bensmaïa, Réda (2006). "Poststructuralism". In Kritzman, Lawrence D.; Reilly, Brian J.; Debevoise, 1000. B. (eds.). The Columbia History of Twentieth-Century French Thought. New York: Columbia Academy Printing. pp. 92–93. ISBN978-0-231-10790-7.

- ^ Poster, Mark (1989). "Introduction: Theory and the Problem of Context". Disquisitional Theory and Poststructuralism: In Search of a Context. Cornell Academy Press. pp. 4–vi. ISBN978-1-5017-4618-five.

- ^ Leitch, Vincent B. (1 January 1996). Postmodernism - Local Effects, Global Flows. SUNY series in postmodern culture. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. p. 27. ISBN978-1-4384-1044-ix. OCLC 715808589. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ Lurcza, Zsuzsanna (2017). "Deconstruction of the Destruktion – Heidegger and Derrida". Philobiblon. Transylvanian Periodical of Multidisciplinary Enquiry in Humanities. 22 (2). doi:10.26424/philobib.2017.22.2.eleven. ISSN 1224-7448.

- ^ "The near cited authors of books in the humanities". Times Higher Education. THE World Universities Insights. 2019.

- ^ Foucault, Michel, 1926–1984. (17 April 2018). The order of things : an archaeology of the human sciences. ISBN978-i-317-33667-nine. OCLC 1051836299.

- ^ Foucault, Michel (xv April 2013). Archaeology of Noesis. doi:10.4324/9780203604168. ISBN978-0-203-60416-viii.

- ^ Foucault, Michel (2020). Discipline and Punish: the birth of the prison. Penguin Books. ISBN978-0-241-38601-nine. OCLC 1117463412.

- ^ Foucault, Michel, 1926-1984, writer. The History of Sexuality : an introduction. ISBN978-1-4114-7321-eight. OCLC 910324749. CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ https://www.google.com/books/edition/Continental_Philosophy_and_Modern_Theolo/0kBNAwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=ane&dq=%22jean+francois+lyotard%22+%22influenced+past%22+%22nietzsche%22&pg=PA166&printsec=frontcover

- ^ Lyotard, J.-F. (1979). The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Cognition. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Printing. ISBN978-0-944624-06-7. OCLC 232943026.

- ^ Luke, Timothy W. (1991). "Power and politics in hyperreality: The critical project of Jean Baudrillard". The Social Scientific discipline Journal. 28 (3): 347–367. doi:ten.1016/0362-3319(91)90018-Y.

- ^ Jameson, Fredric (1991). Postmodernism, or, The cultural logic of tardily capitalism. Durham: Duke University Printing. ISBN0-8223-0929-7.

- ^ Kellner, Douglas (1988). "Postmodernism as Social Theory: Some Challenges and Problems". Theory, Culture & Order. v (ii–3): 239–269. doi:x.1177/0263276488005002003. ISSN 0263-2764. S2CID 144625142.

- ^ Lule, Jack (2001). "The Postmodern Adventure [Book Review]". Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly. 78 (4): 865–866. doi:10.1177/107769900107800415. S2CID 221059611.

- ^ Danto, AC (1990). "The Hyper-Intellectual". New Commonwealth. Vol. 203, no. 11/12. pp. 44–48.

- ^ Sullivan, Louis. "The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered," published Lippincott's Mag (March 1896).

- ^ Loos, Adolf (1910). "Ornament and Crime".

- ^ Tafuri, Manfredo (1976). Architecture and Utopia: Design and Capitalist Development (PDF). Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN978-0-262-20033-two.

- ^ Le Corbusier, Towards a New Compages. Dover Publications, 1985/1921.

- ^ Venturi, et al.

- ^ Jencks, Charles (1975). "The Rise of Postal service Mod Architecture". Architectural Association Quarterly. 7 (iv): 3–14.

- ^ Jencks, Charles (1977). The language of post-modern compages. New York: Rizzoli. ISBN0-8478-0167-5.

- ^ Jencks, Charles. "The Language of Mail-Mod Architecture", Academy Editions, London 1974.

- ^ Farrell, Terry (2017). Revisiting Postmodernism. Newcastle upon Tyne: RIBA Publishing. ISBN978-1-85946-632-two.

- ^ Lee, Pamela (2013). New Games : Postmodernism After Contemporary Art. New York: Routledge. ISBN978-0-415-98879-7.

- ^ Poynor, Rick (2003). No more rules : graphic design and postmodernism. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. p. 18. ISBN0-300-10034-5.

- ^ Drucker, Johanna and Emily McVarish (2008). Graphic Design History. Pearson. pp. 305–306. ISBN978-0-13-241075-v.

- ^ Elizabeth Bellalouna, Michael L. LaBlanc, Ira Marking Milne (2000) Literature of Developing Nations for Students: L-Z p.fifty

- ^ Stavans, Ilan (1997). Antiheroes: Mexico and Its Detective Novel. Fairleigh Dickinson Academy Press. p. 31. ISBN978-0-8386-3644-2.

- ^ McHale, Brian (2011). "Pynchon'southward postmodernism". In Dalsgaard, Inger H; Herman, Luc; McHale, Brian (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Thomas Pynchon. pp. 97–111. doi:10.1017/CCOL9780521769747.010. ISBN978-0-521-76974-7.

- ^ "Postal service, Events, Screenings, News: 32". People.bu.edu . Retrieved 4 Apr 2013.

- ^ McHale, B., Postmodernist Fiction (Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge, 2003).

- ^ McHale, Brian (20 December 2007). "What Was Postmodernism?". Electronic Book Review. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ Kramer, Jonathan (2016). Postmodern music, postmodern listening. New York: Bloomsbury Bookish. ISBN978-ane-5013-0602-0.

- ^ Strinati, Dominic (1995). An Introduction to Theories of Pop Civilization. London: Routledge. p. 234.

- ^ Brown, Stephen (2003). "On Madonna'S Brand Appetite: Presentation Transcript". Association For Consumer Research. pp. 119–201. Archived from the original on nineteen April 2017. Retrieved ane April 2021.

- ^ a b McGregor, Jock (2008). "Madonna: Icon of Postmodernity" (PDF). L'Abri. pp. 1–viii. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 Dec 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ^ Brendan, Canavan; McCamley, Claire (February 2020). "The passing of the postmodern in pop? Epochal consumption and marketing from Madonna, through Gaga, to Taylor". Journal of Business organization Inquiry. 107: 222–230. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.12.005.

- ^ a b Goodchild, Barry (1990). "Planning and the Modern/Postmodern Fence". The Town Planning Review. 61 (2): 119–137. doi:10.3828/tpr.61.2.q5863289k1353533. JSTOR 40112887.

- ^ Jacobs, Jane (1993). The death and life of cracking American cities . New York: Modern Library. ISBN0-679-64433-4.

- ^ a b Hatuka, Tali; d'Hooghe, Alexander (2007). "After Postmodernism: Readdressing the Role of Utopia in Urban Design and Planning". Places. xix (2): 20–27.

- ^ Irving, Allan (1993). "The Modern/Postmodern Separate and Urban Planning". Academy of Toronto Quarterly. 62 (4): 474–487. doi:10.3138/utq.62.4.474. S2CID 144261041.

- ^ Simonsen, Kirsten (1990). "Planning on 'Postmodern' Weather". Acta Sociologica. 33 (1): 51–62. doi:10.1177/000169939003300104. JSTOR 4200779. S2CID 144268594.

- ^ a b Soja, Edward W. (14 March 2014). My Los Angeles: From Urban Restructuring to Regional Urbanization. Univ of California Press. ISBN978-0-520-95763-iii.

- ^ Shiel, Mark (xxx October 2017). "Edward Soja". Mediapolis . Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ Scruton, Roger (1996). Modern philosophy: an introduction and survey. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN0-fourteen-024907-9.

- ^ Dick Hebdige, 'Postmodernism and "the other side"', in Cultural Theory and Pop Civilization: A reader, edited by John Storey, London, Pearson Education, 2006

- ^ "Noam Chomsky on Post-Modernism". bactra.org.

- ^ Craig, William Lane (iii July 2008). "God is Non Expressionless Nevertheless". Christianity Today . Retrieved 30 Apr 2014.

- ^ Pöhlmann, Sascha (2019). The New Pynchon studies. Cambridge. pp. 17–32. ISBN1108474462.

- ^ de Castro, Eliana (12 Dec 2015). "Camille Paglia: "Postmodernism is a plague upon the mind and the centre"". Fausto Mag.

Postmodernism is a plague upon the mind and the heart.

- ^ Wellmer, Albrecht (1991). "Introduction". The persistence of modernity : essays on aesthetics, ethic, and postmodernism. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. ISBN0-262-23160-iii.

- ^ Sokal, Alan D. (1996), "Transgressing the Boundaries: Toward a Transformative Hermeneutics of Quantum Gravity", Social Text, 46–47 (46/47): 217–252, doi:10.2307/466856, JSTOR 466856, archived from the original on 19 May 2017, retrieved 15 March 2008

- ^ Sokal, Alan D. (5 June 1996), "A Physicist Experiments with Cultural Studies", Lingua Franca, archived from the original on five October 2007

- ^ Jedlitschka, Karsten (5 August 2018). "Guenter Lewy, Harmful and Undesirable. Book Censorship in Nazi Germany. Oxford, Oxford University Press 2016". Historische Zeitschrift. 307 (1): 274–275. doi:x.1515/hzhz-2018-1368. ISSN 2196-680X. S2CID 159895878.

- ^ Nagel, Thomas (2002). Concealment and Exposure & Other Essays . Oxford University Press. p. 164. ISBN978-0-nineteen-515293-7.

- ^ Nagel, p. 165.

- ^ Callinicos, Alex (1990). Against postmodernism : a Marxist critique. New York, Northward.Y: St. Martin'due south Press. ISBN0-312-04224-eight.

- ^ Dennett on Wieseltier V. Pinker in the New Republic http://edge.org/conversation/dennett-on-wieseltier-v-pinker-in-the-new-democracy Archived v August 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wolin, Richard (2019). The seduction of unreason : the intellectual romance with fascism: from Nietzsche to postmodernism. Princeton: Princeton Academy Press. ISBN978-0-691-19235-two.

- ^ Daniel Farber and Suzanne Sherry, Beyond All Reason The Radical Attack on Truth in American Police force, New York Times, https://world wide web.nytimes.com/books/commencement/f/farber-reason.html

- ^ Caputo, Richard; Epstein, William; Stoesz, David; Thyer, Bruce (2015). "Postmodernism: A Dead End in Social Work Epistemology". Journal of Social Work Education. 51 (iv): 638–647. doi:10.1080/10437797.2015.1076260. S2CID 143246585.

- ^ Sidky, H. (2018). "The War on Science, Anti-Intellectualism, and 'Alternative Ways of Knowing' in 21st-Century America". Skeptical Inquirer. 42 (two): 38–43. Archived from the original on 6 June 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ Guattari, Felix (1989). "The iii ecologies" (PDF). New Formations (8): 134.

- ^ "The art of disappearing – BAUDRILLARD At present". 22 Jan 2021. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved two March 2022.

Further reading [edit]

- "Graphic Design in the Postmodern Era". Emigre (47). 1998.

- Alexie, Sherman (2000). "The Toughest Indian in the Earth" (ISBN 0-8021-3800-4)

- Anderson, Perry. The origins of postmodernity. London: Verso, 1998.

- Anderson, Walter Truett. The Truth about the Truth (New Consciousness Reader). New York: Tarcher. (1995) (ISBN 0-87477-801-8)

- Arena, Leonardo Vittorio (2015) On Nudity. An Introduction to Nonsense, Mimesis International.

- Ashley, Richard and Walker, R. B. J. (1990) "Speaking the Language of Exile." International Studies Quarterly 5 34, no three 259–68.

- Bauman, Zygmunt (2000) Liquid Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Brook, Ulrich (1986) Chance Society: Towards a New Modernity.

- Benhabib, Seyla (1995) "Feminism and Postmodernism" in (ed. Nicholson) Feminism Contentions: A Philosophical Commutation. New York: Routledge.

- Berman, Marshall (1982) All That Is Solid Melts into Air: The Experience of Modernity (ISBN 0-14-010962-5).

- Bertens, Hans (1995) The Idea of the Postmodern: A History. London: Routledge. (ISBN 978-0-415-06012-7).

- Best, Steven and Douglas Kellner. Postmodern Theory (1991) excerpt and text search

- All-time, Steven, and Douglas Kellner. The Postmodern Plow (1997) excerpt and text search

- Best, Steven, and Douglas Kellner. The Postmodern Adventure: Science, Technology, and Cultural Studies at the Third Millennium Guilford Printing, 2001 (ISBN 978-i-57230-665-3)

- Bielskis, Andrius (2005) Towards a Postmodern Understanding of the Political: From Genealogy to Hermeneutics (Palgrave Macmillan, 2005).

- Contumely, Tom, Peasants, Populism and Postmodernism (London: Cass, 2000).

- Butler, Judith (1995) 'Contingent Foundations' in (ed. Nicholson) Feminist Contentions: A Philosophical Exchange. New York: Routledge.

- Callinicos, Alex, Against Postmodernism: A Marxist Critique (Cambridge: Polity, 1999).

- Dirlik, Arif; Zhang, Xudong, eds. (2000). Postmodernism & Prc. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. ISBN0-8223-8022-6. OCLC 52341080.

- Drabble, M. The Oxford Companion to English Literature, 6 ed., article "Postmodernism".

- Farrell, John. "Paranoia and Postmodernism," the epilogue to Paranoia and Modernity: Cervantes to Rousseau (Cornell UP, 2006), 309–327.

- Featherstone, Chiliad. (1991) Consumer culture and postmodernism, London; Newbury Park, Calif., Sage Publications.

- Giddens, Anthony (1991) Modernity and Self Identity, Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Gosselin, Paul (2012) Flying From the Absolute: Cynical Observations on the Postmodern West. volume I. Samizdat Flight From the Accented: Contemptuous Observations on the Postmodern West. Volume I (ISBN 978-two-9807774-3-1)

- Goulimari, Pelagia (ed.) (2007) Postmodernism. What Moment? Manchester: Manchester University Printing (ISBN 978-0-7190-7308-3)

- Grebowicz, Margaret (ed.), Gender Later Lyotard. NY: Suny Press, 2007. (ISBN 978-0-7914-6956-ix)

- Greer, Robert C. Mapping Postmodernism. IL: Intervarsity Printing, 2003. (ISBN 0-8308-2733-i)

- Groothuis, Douglas. Truth Decay. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 2000.

- Harvey, David (1989) The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change (ISBN 0-631-16294-ane)

- Honderich, T., The Oxford Companion to Philosophy, article "Postmodernism".

- Hutcheon, Linda. The Politics of Postmodernism. (2002) online edition

- Jameson, Fredric (1991) Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Belatedly Capitalism (ISBN 0-8223-1090-2)

- Jarzombek, Mark (2016). Digital Stockholm Syndrome in the Post-Ontological Age. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Printing.

- Kimball, Roger (2000). Experiments confronting Reality: the Fate of Civilization in the Postmodern Age. Chicago: I.R. Dee. 8, 359 p. (ISBN 1-56663-335-iv)

- Kirby, Alan (2009) Digimodernism. New York: Continuum.

- Lash, S. (1990) The sociology of postmodernism London, Routledge.

- Lucy, Niall. (2016) A lexicon of Postmodernism (ISBN 978-1-4051-5077-iv)

- Lyotard, Jean-François (1984) The Postmodern Status: A Study on Noesis (ISBN 0-8166-1173-4)

- Lyotard, Jean-François (1988). The Postmodern Explained: Correspondence 1982–1985. Ed. Julian Pefanis and Morgan Thomas. (ISBN 0-8166-2211-6)

- Lyotard, Jean-François (1993), "Scriptures: Diffracted Traces." In: Theory, Culture and Society, Vol. 21(one), 2004.

- Lyotard, Jean-François (1995), "Anamnesis: Of the Visible." In: Theory, Civilization and Society, Vol. 21(ane), 2004.

- MacIntyre, Alasdair, After Virtue: A Report in Moral Theory (University of Notre Matriarch Press, 1984, 2nd edn.).

- Magliola, Robert On Deconstructing Life-Worlds: Buddhism, Christianity, Culture (Atlanta: Scholars Press of American Academy of Organized religion, 1997; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000; ISBN 0-7885-0295-6, cloth, ISBN 0-7885-0296-4, pbk).

- Magliola, Robert, Derrida on the Mend (Lafayette: Purdue University Press, 1984; 1986; pbk. 2000, ISBN I-55753-205-2).

- Manuel, Peter. "Music equally Symbol, Music as Simulacrum: Pre-Modern, Modern, and Postmodern Aesthetics in Subcultural Musics," Popular Music one/2, 1995, pp. 227–239.

- McHale, Brian (1992), Constructing Postmodernism. NY & London: Routledge.

- McHale, Brian (2007), "What Was Postmodernism?" electronic book review, [i] Archived xviii July 2018 at the Wayback Motorcar

- McHale, Brian (2008), "1966 Nervous Breakup, or, When Did Postmodernism Begin?" Modern Language Quarterly 69, 3:391–413.

- McHale, Brian, (1987) Postmodernist Fiction. London: Routledge.

- Mura, Andrea (2012). "The Symbolic Role of Transmodernity" (PDF). Language and Psychoanalysis (1): 68–87. doi:x.7565/landp.2012.0005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2015.

- Irish potato, Nancey, Anglo-American Postmodernity: Philosophical Perspectives on Scientific discipline, Organized religion, and Ideals (Westview Press, 1997).

- Natoli, Joseph (1997) A Primer to Postmodernity (ISBN 1-57718-061-v)

- Norris, Christopher (1990) What's Incorrect with Postmodernism: Critical Theory and the Ends of Philosophy (ISBN 0-8018-4137-2)

- Pangle, Thomas Fifty., The Ennobling of Commonwealth: The Challenge of the Postmodern Age, Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins Academy Printing, 1991 ISBN 0-8018-4635-eight

- Park, Jin Y., ed., Buddhisms and Deconstructions Lanham: Rowland & Littlefield, 2006, ISBN 978-0-7425-3418-6; ISBN 0-7425-3418-nine.

- Pérez, Rolando. Ed. Agorapoetics: Poetics after Postmodernism. Aurora: The Davies Grouping, Publishers. 2017. ISBN 978-1-934542-38-5.

- Philip B. Meggs; Alston W. Purvis (2011). "22". Meggs' History of Graphic Design (5 ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. ISBN978-0-470-16873-8.

- Powell, Jim (1998). "Postmodernism For Beginners" (ISBN 978-ane-934389-09-6)

- Sim, Stuart. (1999). "The Routledge critical dictionary of postmodern thought" (ISBN 0-415-92353-0)

- Sokal, Alan and Jean Bricmont (1998) Fashionable Nonsense: Postmodern Intellectuals' Corruption of Science (ISBN 0-312-20407-8)

- Stephen, Hicks (2014). "Explaining Postmodernism: Skepticism and Socialism from Rousseau to Foucault (Expanded Edition)", Ockham's Razor Publishing

- Vattimo, Gianni (1989). The Transparent Society (ISBN 0-8018-4528-9)

- Veith Jr., Gene Edward (1994) Postmodern Times: A Christian Guide to Contemporary Thought and Culture (ISBN 0-89107-768-v)

- Windschuttle, Keith (1996) The Killing of History: How Literary Critics and Social Theorists are Murdering Our Past. New York: The Free Printing.

- Wood, Tim, Kickoff Postmodernism, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1999, (Reprinted 2002)(ISBN 0-7190-5210-6 Hardback, ISBN 0-7190-5211-iv Paperback).

External links [edit]

- Discourses of Postmodernism. Multilingual bibliography past Janusz Przychodzen (PDF file)

- Modernity, postmodernism and the tradition of dissent, by Lloyd Spencer (1998)

- Postmodernism and truth past philosopher Daniel Dennett

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'due south entry on postmodernism

thompsonwhory1960.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Postmodernism

Publicar un comentario for "Postmodernism Is a Philosophy of Art That Came to the Fore After the Second World War"